Drinking Water 2024 – Private water supplies in England

Key headlines

Key headlines

A private water supply is any water supply which supplies one or more properties, that is not provided by a water company. Around 1.47% of the population in England use a private supply, which can originate from a range of sources including boreholes, natural springs, and water courses.

Private water supplies are found across most regions of England. The highest numbers are usually found in rural areas where connection to the public mains network may be difficult. Figure 1.1 shows the density of the supplies across England.

Figure 1.1 Private water supply in England

In 2024, local authority records reported a total of 33,133 private supplies in England (33,879 in 2023 and 34,904 in 2022).

A private supply is one which is not connected to the public mains of water companies in England. Typically, these provide water to approximately 1.47% of the population in England covering not just domestic supplies to households but also those to commercial premises such as farms, bed and breakfast accommodation, holiday lets, hotels, sporting clubs, manufacturers and other businesses. The contribution to the economy as well as the health and welfare of a notable population of 849,800 is significant.

The standards and principles of regulation are the same for both public and private supplies, in order to protect public health equitably, regardless of the source of the water supply. The expectation is that the level of quality should be the same as public supplies, however, small private or community supplies are often of a poorer quality, as evidenced by the relative numbers of indicators of faecal pollution. E. coli was found in 4.46% of tests, compared to the public mains supply (approximately 0.02%).

The reasons for this are complex but their small scale is one of the main challenges. The cost and resources required can be disproportionate when maintaining a small supply. For instance, technical knowledge covering geology and catchment science, borehole construction, treatment and distribution engineering as well as water quality and risk assessment are highly specialist skills which are often inaccessible to private supply users, but are essential for the appropriate design, maintenance and operation of a private supply. These challenges can be exacerbated by property and ownership arrangements where a source may not be in the control of the user, and it may not be known with whom responsibility for the running and maintenance of the supply lies. Sometimes no-one accepts responsibility for a supply, leading to its neglect. In these instances, necessary safeguards to protect water quality, such as a lack of adequate maintenance and poor management practices can be absent.

The principle of water supply regulation is one of self-regulation by owners/users/controllers, and of independent scrutiny by the regulator, which for private supplies is the local authority.

Environmental health staff of local authorities are essential to regulating private supplies. They have a legal duty to keep a record of those supplies that are known and to conduct water quality and sufficiency risk assessments. Risk assessments are fundamental to identifying risks, and how these might be observed, managed, and controlled though a plan to protect public health and sufficiency. This helps users become better informed to manage supplies safely and, where necessary, carry out improvements to mitigate any risks identified to water quality and supply.

It is becoming ever clearer how vulnerable some private water supplies are as the climate changes, and this is evident by the increasing numbers that run dry in periods of drought and those being affected more acutely by environmental pollution. Risk assessment should identify these supplies, and contingency plans should be established. This vulnerability extends to include supply interruptions which may be caused by infrastructure failures such as pipe bursts. The lack of resources to quickly react to these failures by completing fixes and replacements, or to provide suitable alternative supplies utilising existing pipework or via other means such as tankers and bottles, means that general resilience of these supplies is poor.

In 2024, due to software incompatibility that caused a problem with the reporting process, the Inspectorate is unable to include test results for the indicator parameter colony counts (number per 100 mL at 22 degrees centigrade).

In 2024, 2.50% (5,728 of 229,216) tests by the local authorities in England were found not to be meeting one or more of the standards for wholesomeness. Figure 1.2 shows that overall, there has been a reduction in tests failing the regulatory standards. However, these figures must be caveated because the overall number of tests carried out is below that which would be expected for the number of private supplies recorded in England. Due to the data error, the Inspectorate has removed all data associated with colony counts across all years in all charts within this report. This allows the data to be comparable over time for this year’s report, however, this means that a comparison should not be made between this year and previous years’ reports.

Figure 1.2 Percentage of tests failing to meet the standards for wholesomeness and the number of tests

At least 4.46% of tests in England during 2024 showed faecal contamination, with 4.46% (560 of 12,559) of samples tested found to contain E. coli and 5.40% (374 of 6,921) containing Enterococci. These organisms are almost exclusively found in faeces, indicating a potential danger to the health of those drinking this water.

The percentage of samples collected from supplies found to be contaminated by E. coli and Enterococci, in the period 2014-2024 is shown in figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Percentage of supplies samples in 2014-2024 found to contain E. coli or Enterococci

Figure 1.3 shows a decrease in the number of supplies which were sampled in 2024 and found to contain E. coli or Enterococci. Looking at the six year’s data between 2018 and 2024, the results are flatter, but there is still variability in the data. An investigation would need to be conducted to determine the reason for this, however there is no overseeing body within Government to carry out this function. It also must be noted that the testing regime is not uniform year on year therefore it is expected and can be seen that there is a backdrop of fluctuating sample numbers and a similarly fluctuating number of failures which may be influenced by sample numbers and the sites from which they were taken. Summing up the number of consumers at private supplies where E. coli and/or Enterococci have been found equates to 533 supplies where faecal contamination was found in the supply, with 16,908 people drinking this water.

One of the key principles of the Private Water Supplies (England) Regulations 2016 (as amended) (the Regulations) is to carry out a risk assessment to establish whether there is a potential risk of supplying water that may be unwholesome or would constitute a potential danger to human health. The Regulations have advanced from the compliance-based methodology of end point monitoring, to minimise the dependency on a sample which may be as infrequent as once in five years providing less assurance of a safe and secure supply. Risk assessments are a proactive approach to identify the risks, which are often visible to the trained and competent assessor, resulting in simple action to put a method of control in place.

The importance of risk assessment will become more apparent as supplies are now reaching the point where there are more than three years’ worth of sample results allowing some to qualify for a potential sample frequency reduction for some parameters. When sampling frequencies are reduced, risk assessment will be the primary mechanism for quality and sufficiency issues to be identified and mitigated. In England in 2024, 1193 out of 8337 regulation 9 supplies were subject to reduced testing frequencies. Local authorities may reduce sampling frequencies for all parameters apart from E. coli provided three years’ test results show concentrations of the parameter at less than 60% of the standard. They may also cease testing altogether for any parameter apart from E. coli, provided concentrations are less than 30% of the standard for three years. In both cases, the supplies’ risk assessments should indicate that there is no risk of these concentrations worsening. Additionally, the supplies should have a level of periodic testing, plus the required reviews of their risk assessments in order to identify any likely or actual change in risk or concentrations over time.

Point of use testing will remain a useful part of monitoring when measuring efficacy following a risk assessment, or more widely as a measure of general improvement or otherwise of an intervention strategy.

Each local authority must carry out or review a risk assessment of each qualifying private water supply system in its area at least every five years, or earlier if it is considered that the supply presents a risk. The Inspectorate has developed a set of risk assessment tools to help local authorities comply with their duties under regulation 6. These can be found on the Inspectorate’s risk assessment web page. A Microsoft Teams forum has been set up to facilitate training and videos are available through this group.

Local authorities report information on risk assessments and enforcement action to the Secretary of State in two ways; in the annual data return, and through summaries of risk assessments. Also, throughout the year, they must submit copies of notices served.

To date, the numbers in the annual data returns have never matched the number of documents received, with under-submission of risk assessment summaries and notices remain a consistent issue. Some explanation is provided in the following section; however, local authorities are reminded that documents can either be redacted or sent by a secure file transfer to preserve data privacy.

Where any private supply of water intended for human consumption constitutes a potential danger to human health, the local authority must serve a regulatory notice on any or all persons involved with the supply. The main aim is to protect public health, so timely action is essential.

The local authority must consider the risk assessment, all the relevant local circumstances and any advice from United Kingdom Health Security Agency (UKHSA). Any site-specific local agreements, covenants or deeds specifying responsibilities for specific aspects of the supply, or its management should be considered.

The 2024 data indicates that across England, the number of private supplies which required a risk assessment that had been risk assessed within the previous five years was 5,143; covering 39% of supplies in scope. The absolute number of supplies with an ‘in-date’ risk assessment has increased, and the percentage of supplies with an ‘in-date’ risk assessment, where one is required, has also marginally increased.

This indicates that local authorities are not making significant progress in moving towards 100% coverage. Figure 1.4 shows that for the past three years, the majority of private water supplies that should be risk assessed, either have never been, or were risk assessed more than five years ago.

Figure 1.4 Risk assessments at regulation 8, 9 and 10 (shared) supplies

In 2024, where a sample was taken for E. coli, this parameter was found in 106 supplies without a risk assessment or where a risk assessment was not carried out in the last five years. With 39 fewer supplies containing E. coli without a risk assessment than the previous year, this is a welcome improvement. Nevertheless, it remains disappointing that in these cases, a sample result revealed the contamination, because the consumer would have been unsuspecting and would not have been acting to protect their own health prior to the water being tested.

The better-practice approach is for a risk assessment to identify sources of contamination and pathways to the supply. This approach should identify all potential contaminants and not rely on the results of a spot sample which cannot be guaranteed to detect all contaminants at the point a sample is taken. The contaminants being tested for may be limited, and concentrations of those which are tested for, may not be at their worst case. Most worrying is that where samples are taken in the absence of a risk assessment, the consumer continues to use the water for drinking and cooking while the samples are analysed. Where a local authority receives a positive result for bacteriological tests in the absence of a supply risk assessment, the supply should be prioritised in the local authorities’ risk assessment programme.

In this 14th year of reporting against this current regulatory framework, local authorities are still not fully delivering their statutory duties, which aim to protect public health.

Understanding the state of private supplies in England relies on the provision of information and data by local authorities. In turn, the analysis of this information allows national reporting to direct policy change in pursuit of improving the quality of private supplies. However, this has been impeded by late or absent returns to the Inspectorate of sample data, summaries of risk assessments and notices which have been served.

To remedy this issue and to modernise the risk assessment tool provided to local authorities, the Inspectorate commissioned a new online system to replace the Excel risk assessment tools, and parts of the information submission requirements. The plan to roll out the system in a beta phase, was put on hold during 2022. Due to significant challenges with the partially developed online system, the Inspectorate has concluded that a bespoke system utilising Defra’s Digital, Data and Technology security service will be required. However, difficulties securing funding will affect the Inspectorate’s ability to collect private water supplies data going forward.

During 2024, the Inspectorate gathered data through the annual data return which is a statutory reporting requirement of local authorities.

Under regulation 14 of the Regulations, local authorities must keep records of every private supply in its area and submit these to the Inspectorate by 31 January each year.

For the reporting year 2024, a submission was received from 207 local authorities, which is six fewer than the previous year. Note that colony count test numbers have been removed from all years in this report’s charts.

In 2024, local authorities carried out 229,216 analyses of private water supplies samples. This is a decrease of 3.8% on the previous year and 6.61% less than the numbers taken in 2019 pre-pandemic. Figure 2.1 shows a general increase in samples taken since 2014, with 2020 representing an exceptional year due to the impact of the pandemic. There appears to be a gradual decline from the number of tests in 2022 to today, increasing the shortfall for private water supplies. Due to the risks associated with private water supplies, increasing resources to reduce the shortfall would be beneficial to protecting public health.

Figure 2.1 Number of tests from 2014 to 2024

When analysing the test data to produce this report, the Inspectorate identified an anomaly. There was a much greater number of colony-count failures than previous years. The standard for colony counts (specifically three days at 22 degrees centigrade) which is an indicator parameter, is ‘no abnormal change’. There is therefore no ‘prescribed concentration or value’ (PCV). It is the responsibility of local authorities to determine what would be an abnormal change for any particular private water supply. An abnormal change may indicate a problem with the quality of the supply. In public supplies, it is not uncommon to see colony counts between tens and hundreds, which are a stable background levels for a supply or perhaps an asset such as a treated water reservoir within distribution. Investigating this anomaly further, the Inspectorate found that a problem with the validation macros of the data return Excel template meant it would not allow a colony count value of greater than zero (in effect a count of one or more) to be entered as a ‘pass’. Unfortunately, many local authorities decided the best course of action was to change these results to a ‘fail’ to eliminate the spreadsheet error. This was unnecessary, as the database validation routine was working correctly, and would have accepted these results as passing tests, had the Excel template been uploaded. The Inspectorate will investigate options to rectify this incorrect data with local authorities affected, during 2025. Due to this data error, colony count test data and information have been removed from charts and figures in this report.

At an aggregate scale, it is clear that private water supplies are not being tested at the frequencies required by the Regulations. It is vitally important for the regulatory testing regime for a supply to be determined and then met each year, or every five years, as appropriate. This validation monitoring provides a baseline to measure the overall quality of those supplies and the effectiveness of mitigation measures. Other sampling, which could be called ‘investigatory’, can be recorded as such on the annual data return. Figure 2.2 illustrates the issue of incorrect testing frequencies for one parameter, E. coli. At regulation 9 supplies, E. coli should always be tested at the Group A frequency stipulated in the schedules to the Regulations. Samples taken as group A must be recorded in the data return as such.

In 2024, 44% of regulation 9 supplies were tested at the correct frequency for E. coli according to the volume supplied. This is an improvement on 34.3% in 2023. A further 9% were tested at a higher frequency than that required by the Regulations. However, the remaining 47% of supplies had fewer tests than required by the Regulations, 4% of which were under-sampled and 43% not sampled at all. In 2023, 53% of supplies were not tested for E. coli at all, so there has been a welcome step-change in local authorities testing regulation 9 supplies which, as large supplies that may also be used in commercial or public activities, are the supplies which pose the most potential for risk to public health.

Figure 2.2 Regulation 9 supplies tested for E. coli at Group A frequency

The Inspectorate attends various regular meetings and events each year. A common point of discussion at these meetings is risk assessments and test data from third parties. The Inspectorate can confirm that it does not receive data or any other information on private water supplies from third parties. The only data submission process in place is the one managed directly with local authorities.

If local authorities are using third parties to conduct private water supplies sampling and testing, the requirement of schedule 3 part 1(4) of the Regulations for an agreement (contract) to be in place must be met. This contract between the local authority and the provider must ensure that the requirements of the Regulations are met, and that any breach of those requirements is reported to the local authority within 28 days.

While there is no similar direct provision in the Regulations for local authorities to use third parties to conduct risk assessments, the very nature of conducting a holistic risk assessment means drawing on the information and knowledge of others who are informed about the supply. Though, third parties may be major contributors to the risk assessment process, local authorities still carry the responsibility for the risk assessment overall, and are the only entity empowered to act in response to the risk assessment’s conclusions.

Local authorities bear the sole obligation for reporting data and information to the Secretary of State under the requirements of regulation 14 and schedule 4 of the Regulations, therefore the Inspectorate will not accept data or information from third parties where no agreement is in place. Regulation 8 supplies would be the most common supply type that may involve a third party. Some of these onward supplies serve a large number of consumers, with the third-party distributors often being large organisations or companies. The Inspectorate has been involved in informal discussions when local authorities have cited that these third parties either refuse to share their test data or assure the local authority that test data is being shared with the Inspectorate. As the Inspectorate does not receive any data or information from third parties, this indicates a potentially large data gap which is likely due to missing third-party data.

Table 1 A summary of the percentage of samples failing for various microbiological and chemical parameters.

|

Microbiological parameters | ||

| 2023 | 2024 | |

|

E. coli |

4.93 |

4.46 |

|

Coliform bacteria |

13.20 |

10.31 |

|

Enterococci |

5.98 |

5.40 |

|

Clostridium perfringens |

5.05 |

4.68 |

|

Chemical parameters | ||

|

2023 |

2024 | |

|

Odour |

4.37 |

4.01 |

|

Taste |

3.78 |

3.94 |

|

Manganese |

4.42 |

4.79 |

|

Iron |

4.15 |

3.81 |

|

Aluminium |

1.11 |

1.14 |

|

Turbidity |

0.94 |

0.96 |

|

Colour |

1.15 |

1.52 |

|

Lead |

2.69 |

2.38 |

|

Nickel |

3.73 |

2.36 |

|

Pesticides |

0.17 |

0.08 |

|

Fluoride |

1.01 |

1.69 |

|

Nitrate |

6.54 |

8.42 |

|

Nitrite |

1.05 |

1.34 |

|

Others |

2.90 |

3.04 |

The detection of specific indicator micro-organisms means that a supply is contaminated. When E. coli, Enterococci and to a lesser extent Clostridium perfringens are found, this suggests that the contamination may be faecal in origin. Faeces often carry micro-organisms including bacteria, viruses and parasites which are harmful to health and when a faecal indicator is found, this water should not be consumed.

Table 1 shows that during 2024, in England more than one in 25 supplies may be unfit for consumption and pose a risk to health containing E. coli. Whilst coliforms are not always a direct indicator of faecal contamination, they still indicate that there is a route for contamination to enter the supply and that contamination has not been removed by treatment. This was found in one in 10 tests. Protection of supplies from contamination is critical to protecting public health. Should a supply be found to contain the presence of faecal matter, the local authority is obligated to investigate in accordance with regulation 16 of the Regulations.

Taste and odour failures could be caused by the quality of the source water or develop as water passes though the distribution system. How consumers describe the taste or odour can help identify the cause with descriptions such as ‘earthy’ or ‘musty’ pointing to possible algal problems in the source water and ‘woody/pencil shavings’ suggesting the presence of black alkathene pipework, to use a couple of examples.

Lead and nickel were detected in 2.38% and 2.36% of tests respectively. For lead this is a decrease compared with 2.69% in 2023, 3.63% in 2022. Lead is a neurotoxin that particularly affects children and can cause health effects in adults including chronic kidney disease, raised blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Where lead is detected above the standard, local authorities must serve a regulation 18 notice to secure actions to protect the health of the consumers. The most robust long-term solution is the removal of any lead pipework, lead-containing fittings, and lead solder. The World Health Organization has recently published their refreshed technical brief on lead, which can be found on its website.

Nickel is largely detected because of nickel plated domestic fittings such as taps. Sometimes the source is not as obvious and could be under sink mixers and temperature regulators. Consumers should be advised to replace these fittings where failures of the standard occur.

Iron, manganese and aluminium can be seen to have failed standards in 3.81%, 4.79% and 1.14% of tests respectively. All these metals can be found naturally occurring in sources waters. Local authorities should consult with UKHSA to determine whether the concentration of these metals pose an immediate danger to health, and if so, must serve a regulation 18 notice. Should the presence of these metals not be deemed a potential danger to health, local authorities can still act under section 80 to compel the relevant persons to make the supply wholesome and acceptable for all domestic purposes which includes washing and laundry.

Turbidity and colour are seen to have been found in concentrations above the standards in 0.96% and 1.52% of tests respectively. Turbidity can reduce the effectiveness of disinfection so a detection of turbidity in excess of the standard should trigger an investigation to determine the cause, followed by the appropriate course of action under regulation 18 or section 80 of the Water Industry Act 1991 (the Act) to carry out improvement actions. Colour detections are usually caused by compounds which arise from the catchment of the source waters and can be removed by suitable treatment processes.

A short-term increase in colour and/or turbidity can be a result of high rainfall mobilising humic substances in source waters. If these short-term occurrences become more frequent, this may be a result of long-term changes in weather patterns.

The data return suggests that 465 supplies have been risk assessed, including the risk posed by PFAS. This is reduction on last year when 625 were said to have PFAS risk assessments.

The Environment Agency has continued to write to local authorities and supply owners/users when a private water supply on its ground water monitoring programme is found to contain PFAS in concentrations above the limit of detection. Local authorities are encouraged to refer to the Inspectorate’s guidance on PFAS, and to investigate these supplies to evaluate the level of risk posed to consumers.

Within the test data submitted by local authorities, there were three supplies with concentrations of PFAS within tiers 2 or 3 of the Inspectorate’s guidance, requiring investigation and remedial action. One supply is known and is a food production premises. The Inspectorate has liaised with the local authority regarding this supply, and it is active in the supplies’ catchment area, with a good understanding of the risk. The other two sites have concentrations in tier 2. One is a regulation 10 shared supply in Adur and Worthing Council’s area which does not have a risk assessment that includes PFAS. The last risk assessment was completed in 2014 and therefore its five-yearly review is overdue. The other is a regulation 9 supply in Spelthorne Borough Council’s area, which did have a PFAS risk assessment conducted in 2024. The Inspectorate encourages local authorities to submit PFAS data in annual data submissions. PFAS samples will be regarded as ‘investigatory’ samples as tests are not required under the Regulations. Local authorities assessing PFAS risk may wish to consult the Environment Agency open data which holds PFAS test data for its groundwater monitoring sites. Some of the sites are private water supplies, and others may be located near to private water supplies. The quantitative results would be most useful, and grid references of the sample points are included.

Water sample results provide insight into the quality of water at the time the sample was taken and can act as an indication that further investigation is needed.

Local authorities submit sample results to the Secretary of State annually. A small subset of results provided each year exceed the regulatory limits by a significant magnitude. Not all of these figures have a commentary provided with them in the data return, which would be an opportunity to explain exceptional circumstances.

Five results for ammonium above 5 mg/L were received, 10 times above the regulatory limit.

Excess ammonium within distribution networks encourages the development of nitrifying bacteria, which can subsequently increase the concentrations of nitrite. Seven results above 10 mg/L of nitrite were reported. The limit at the consumer tap is 0.5 mg/L.

Nitrite is a health-based parameter as babies and younger children are susceptible to develop methaemoglobinaemia at concentrations of nitrite above the regulatory limit. Nitrite is an oxidant and so oxidises iron in haemoglobin (in blood) to methaemoglobin. This means that there is not enough iron in haemoglobin to transport oxygen in the body, resulting in symptoms such as a blue discolouration to the skin (known as cyanosis) and in severe cases, it can result in death.

There was one sample received for gross alpha, seven times the regulatory limit of 0.1 Bq/L. The regulatory limits on gross alpha and gross beta are in place due to the impact on indicative dose of some radionuclides. Some radionuclides will exceed indicative dose when they produce a gross alpha result of 0.1 Bq/L, which is why it is critical to understand the source of radioactivity once gross alpha or beta is exceeded. This is done through an indicative dose test (also known as speciation) which provides more detailed information so that decisions can be made regarding the health effect of the radioactivity as well as possible treatment.

Five samples taken from the same location for benzo[a]pyrene were reported as above 0.42 µg/L against a standard of 0.01 µg/L. A further sample over 400 µg/L was reported from a different site. Benzo[a]pyrene is present in the regulations because it is a carcinogen. Therefore, seeing multiple results above the limit at the same site is of concern. If multiple samples from different sources exceed the limit with no explanation from the risk assessment, the laboratory should be consulted for further advice on the validity of the results. Local authorities should also check to ensure that any qualifiers provided by the laboratory for the data are included in the annual data return as this can greatly affect the interpretation of any results.

Ten results over 100 µg/L were reported for lead. There is no safe level of lead with the best solution to the presence of lead pipework being its removal. Lead is also present in brass fittings to varying levels. An investigation should be undertaken by the local authority for all lead results above the regulatory limit and should be considered at values below that.

In England, a number of strontium results over 4000 µg/L were reported. There is no regulatory limit for strontium; however, strontium can be a radioactive element. The risk of radioactive strontium, which has a different health-based limit, should therefore be assessed through the risk assessment process. Risks from radioactivity should be discussed with UKHSA in England. The possibility of the presence of radioactive strontium would indicate the need for further radioactive testing.

Sixteen results over 20 NTU were provided for turbidity. Turbidity indicates how much the light reflects within a sample of water. The higher the turbidity, the more difficult it is to fully disinfect the water. This includes with ultraviolet light. For supplies with high turbidity the risk assessment should consider the effectiveness of disinfection and the risk of disinfection byproducts.

One sample in England returned a high result for vinyl chloride, which was hundreds of times the regulatory limit. This value is usually controlled by product specification, limiting the material in products coming into contact with water. Vinyl chloride monomer is used in the production of PCV (polyvinyl chloride). This is mostly used in plastic pipework, but it can also be formed from the breakdown of other chlorinated compounds, something which is often noted in water supplies close to landfills. Any results above or close to the regulatory limit for vinyl chloride should be fully investigated to ascertain the source of the increased monomer concentration as this compound is associated with various health risks.

Several results of the pesticide DDT were reported. DDT was banned in 1984 in the UK. To receive nine results at exactly the same concentration, six times the general pesticide limit, is extremely unusual. Any positive DDT result should be investigated as it would indicate a change to the catchment which has encouraged the release of pesticide which has been stored for decades. There may therefore be other catchment risks not revealed by the sampling regime.

Eleven fluoride results were reported of 150 mg/L or above. As well as being scientifically very improbable, these concentrations present a significant health risk and should have been investigated immediately, especially from a regulation 9 supply supplying food products to the general population.

However, the more likely explanation is that these results have been supplied in a different unit to those required by the regulatory data input. It is always important for local authorities to check the regulatory unit requirements prior to data submission as results may need to be converted prior to submission. Laboratories occasionally report some parameters in nanograms per litre when the regulatory limits are provided in micrograms per litre.

In 2024, the percentage of private supplies which have an in-date risk assessment are:

• Private distribution systems (regulation 8 supplies) 25.5%.

• Large, commercial and public use (regulation 9 supplies) 45.9%.

• Small supplies (regulation 10 supplies) – 27.8%.

In total, 13,092 supplies require a risk assessment, and only 5,143 (39.3%) have one that has not expired. For all supply types other than single dwelling supplies, local authorities have been required to complete risk assessments since 2010. It is concerning that, 10 years after the introduction of this requirement, there is still a significant proportion (31.6%) where the risk assessment has exceeded the requirement for a five-yearly review and a critical 29.1% which have never had a risk assessment where users remain unsuspecting that their supply may contain faecal contamination.

In addition, supplies to untenanted single dwellings (regulation 10[3] supplies) are only risk assessed upon the owner’s request and 14.3% on a risk assessment programme have in-date risk assessments.

In 2018, a change in the Regulations brought about the requirement for local authorities to provide a summary of the results of risk assessments to Ministers (in practice the Inspectorate) within 12 months of having carried out the assessment.

During 2024, the Inspectorate received 200 risk assessment summaries from 23 local authorities. This is an almost identical number as received during 2023. There are still 188 out of 211 local authorities in England that submitted data on private supplies who have not met the statutory reporting requirements regarding risk assessments in 2024. We would encourage local authorities to at least programme an annual exercise to submit the risk assessment summary pages to the Inspectorate, perhaps to coincide with the annual data return submission.

A review of the submitted risk assessment summaries suggest that some local authorities are only conducting reactive risk assessments following sample failures. Risk assessments and associated mitigation measures should be verified by sampling, and not the other way round. Data including sample results can be used to inform a risk-based prioritisation of risk assessments and it may be prudent to review risk assessments following sample failures. However, the risk assessment process must be a proactive one and not a process where risk assessments are only conducted where sample failures have occurred.

Protection of the source and the abstraction point were common root causes of risk identified as part of local authority risk assessments. The need for remedial actions to protect the source of a private supply from risk of contamination from livestock, slurry, pesticides, and septic tanks featured repeatedly on the summaries submitted to the Inspectorate. Similarly recurrent were actions required to secure spring chambers, headworks, and buildings from drainage issues, unauthorised access and vermin.

Ultraviolet (UV) systems are commonly used for disinfection in private water supply systems. The efficiency of UV systems used for disinfection are affected by the water quality and the flow rate through the system. High turbidity can shield pathogens from the UV dose and an improper unit for the required flow rate may result in an insufficient UV dose applied. Local authority assessors noted risks from a lack of maintenance, resilience and control in some systems. Common mitigations required the need for intensity monitors, alarms and shutdowns in case of unit/bulb failures, power interruptions, or high turbidity in the influent water which may inhibit UV disinfection. Such controls would reduce the risk of partially or non-disinfected water being available for consumption.

The absence of regular inspection, cleaning, and maintenance of water storage tanks was frequently flagged as a risk in the risk assessment summaries. For comparison, treated water tanks (storage reservoirs) are an integral part of public water supply networks. Water companies conduct external inspections annually to identify risks from ingress and contamination. Furthermore, water companies must conduct internal inspection, cleaning, and remedial maintenance at a frequency dependent on the risk and the quality of the influent water. Assets such as water tanks are not in stasis and require regular intervention to maintain operability.

Local authorities are required to serve notices served under the legislation to Ministers (in practice the Inspectorate) in accordance with regulation 18 where supplies are a potential danger to human health. They may also serve notices under section 80 of The Water Industry Act 1991 (the Act) where supplies are unwholesome and or insufficient.

In 2024, the Inspectorate received 114 notices served under regulation 18 of the Regulations for supplies that were considered a potential danger to human health. The data return indicated that 231 had been served in 2024. Forty-seven notices were served under section 80 of the Act according to the data return, but only four were received by the Inspectorate.

Figure 2.3 Regulation 18 notices served versus those submitted to the Secretary of State

Most notices are historically served in response to a failure of a microbiological standard, with a small minority for failures of other standards. In 2024, 69 out of the 114 notices submitted were served for failures of microbiological standards.

The tenet of the Regulations is one of proactive risk assessment to prevent failures and a risk to health from ever being realised, and it is welcome to see that 11 were served due to actions from this process and one notice was put in place due to a lack of risk assessment.

However, local authorities still appear to be predominantly reacting to sample results, rather than proactively eliminating the problems that would result in a sample failure. The use of a proactive risk assessment, and if necessary, a notice in this context, is to protect users before an incident occurs so they are not unsuspecting, and they can be responsible for protecting their own health.

Table 2 Notices served

| Reason for serving the notice | Number |

| Risk assessment | 11 |

| Lack of risk assessment | 1 |

| Bacteria | 69 |

| Nitrate | 16 |

| Multiple parameters | 9 |

| Multiple metals | 1 |

| Arsenic | 3 |

| Fluoride | 2 |

| Manganese | 1 |

| Nitrate and nitrite | 1 |

| Total | 114 |

Sixty-nine notices were served for microbiological drivers. The majority of these required treatment systems to be serviced or the installation of additional treatment.

Three mentioned making changes to the source or source protection, which is worth considering for some supplies where changes in the catchment have been noted as part of the risk assessment and investigation following a sample failure.

Some notices mentioned the use of UV as a method of disinfecting the water. It is worth noting that where supplies are at risk of viral contamination, such as faecal contaminated supplies, UV disinfection may not be suitable when used alone and additional treatment for viral removal or inactivation may need to be considered through the risk assessment process.

The Inspectorate continues to work with stakeholders on this complex subject. Inspectors have attended health liaison meetings across the country to speak about the change to the technical brief on regulation 8.

The Water Health Partnership for Wales has formed a ‘task and finish’ group to look at this topic and produce an agreed plan between local authorities and water companies on how to identify these supplies, then subsequently risk assess and sample them.

In 2022, the Inspectorate wrote to water companies reminding them of their responsibilities associated with the onward distribution of their supplies, particularly the requirements of section 74 of the Water Industry Act 1991. In 2025, the Inspectorate has sought a data return from water companies to ascertain progress with complying with these requirements.

The Inspectorate meets with the sampling certification body at least twice each year. This is primarily to monitor progress with the implementation of the scheme across the local authorities in England and Wales, and to identify any areas that are causing setbacks. The Inspectorate also attends training sessions to maintain an independent view of the scheme’s implementation. The scheme appears to be well embedded, and numbers of individuals certified continues to increase.

By the end of 2024, 115 local authorities had at least one certified sampler. Some of the remaining local authorities may use laboratory samplers, in which case they would not need in-house certified samplers. However, it is important to note that any samples taken and then analysed under part 3 (Monitoring) of the Regulations, must be done so in accordance with schedule 2 parts 1, 2 and 2A, which requires compliance with ISO 17024 or ISO 17025. In 2024, 93.6% of tests met these requirements.

In 2023, the certification body introduced online training, reducing the need to find suitable training venues and removing the need for delegates to travel. The practical element of the assessment then follows and is carried out at a mutually convenient later date, in the field.

In February 2024, the certification body was audited by UKAS. No issues were raised.

The Inspectorate is satisfied that local authorities are generally complying with the regulatory requirement for samplers to be accredited under an ISO 17024 scheme (or equivalent). The scheme is now established and certification for the sampling of private water is an accepted necessary requirement. General feedback by delegates shows that the training is well received and provides essential training to maintain a common and recognised national standard.

Table 3 Figures on the ISO 17024 scheme covering England and Wales

|

Total no. of samplers to date with valid/in date certificates. |

332 |

|

No. of samplers certified for the first time this year? |

54 |

Total no. of individual sampler 36-month recertifications carried out this year. |

108 |

|

Total no. of trainees that failed the assessment first time during this year (including recertifications). |

8 |

|

Total no. samplers that have out of date certification. |

56 |

|

Total no. of sampler audits carried out this year? |

44 |

|

How many certified samplers were not audited within the 18-month window this year? |

19 |

|

How many certified samplers to date have never received at least one audit? |

35 |

|

No. of local authorities with at least one certified sampler to date. |

115 |

The Inspectorate publishes a variety of case studies on private water supplies on its website. These cover a range of scenarios and subjects, which are largely derived from enquiries to the Inspectorate, either from local authorities or private water supply users. Some come from third parties, including lawyers, agencies, local councillors and MPs. These case studies show and share the range and diversity of issues and circumstances that can come about in relation to private water supplies. The additional benefit of their publication on the Inspectorate’s website is to make available the learning that can be taken from them.

There were five case studies compiled in 2024. These can be found on the website at Drinking Water Inspectorate (dwi.gov.uk)

This case study describes the difficulties that arose during a period of insufficiency on a private supply that until 2017 was a public supply. In moving from being a public supply to a private one, it created several new challenges for those responsible for its maintenance and upkeep under private supply legislation. These challenges caused considerable impact to consumers during this period of insufficiency. These issues are not uncommon to shared private supplies and are exemplified in this case study. This case study also shows that whilst the switch from a public supply to a private supply resolved some of the problems that led to it, it created others which resulted in risk to consumers. These were not necessarily anticipated and/or proactively managed to prevent or mitigate these risks for a variety of reasons, when the switch was made. Often this is due to financial or resource limitations, or where the local authority has not used its powers to facilitate mitigation to prevent or adequately manage the risk.

In the Inspectorate’s report for the year 2013, it described the reasons why a newly installed private water supply serving a large regional hospital was never fully commissioned into use, despite the considerable costs it incurred. This case had some bearing on the revision of the regulations in 2016. The Inspectorate revisited this case in 2024. It learned that the then new borehole at the hospital was never used as intended. Therefore, the considerable time, effort and costs were unfortunately and ultimately lost to this well intended project. This case study challenges the effectiveness of current private water supply regulation in protecting consumers in a way that is equitable to public drinking water supplies.

This case study exemplifies why prospective buyers of property served by a private water supply should consider any implications or potential risks associated with the supply prior to any purchase. Supply arrangements vary from one to another and the responsibilities in their management and maintenance are not always clear or documented. This can cause later difficulties and disagreement between the parties involved when situations change. Unfortunately, this is because any potential impacts these discrepancies may cause are often overlooked because robust checks are not made during the property conveyancing process. This case study shows one such example.

This case study concerns a regulation 9 supply providing water for domestic purposes to 300+ consumers. Sampling by the local authority highlighted a rising trend in arsenic concentrations, which presented a potential danger to human health. The local authority did not however investigate the root cause of the arsenic in accordance with regulation 16 or serve a regulation 18 notice to secure a permanent, long-term solution as the Regulations required them to do under these circumstances. Instead, when test results were over the maximum concentration stipulated in the Regulations, the site would be temporarily switched over to a back-up mains water supply until maintenance on inadequate treatment was completed. This reactive approach is contrary to the proactive risk-based approach that the Regulations require as it does not fully mitigate the risk or address the root cause in the long term to protect consumers.

It is not a legal requirement for consumers, owners or indeed anyone, to register private water supplies with the local authority. Many choose not to, whilst others are just not aware of the Regulations and/or that the Regulations place duties on local authorities to test and risk assess them (excluding those that serve single dwellings exclusively). If a local authority is not made aware of a supply in its area, it cannot carry out its duties as required to protect the consumers of that supply. This presents a potential risk can have unforeseen consequences as this case study illustrates.

The provision of technical briefings on the Inspectorate’s website is a fundamental role in relation to private water supplies currently fulfilled by the Inspectorate. The main purpose of this is to set out an interpretation of the Regulations to assist local authorities in discharging their duties as regulators in a consistent and compliant manner. However, these briefings are also made available for other stakeholders, including supply users, who may wish to understand how the Regulations apply to their specific circumstances. Technical briefings are also provided on private water supply management, water treatment, and advice which is aimed specifically at prospective buyers of premises served by a private water supply.

In Drinking Water 2023, the Inspectorate reported that it had revised its technical briefing on regulation 8, setting out the reasons why this was necessary. This followed consultation with legal professionals to clarify what did and did not constitute a regulation 8 private water supply in law.

The review that led to this revision identified several discrepancies and inconsistencies in the wider legislation in relation to regulation 8. In 2024, the Inspectorate raised these matters with Defra as they were causing increasing concern and confusion amongst various stakeholders, including the economic regulator and local authorities. For example, it became apparent that whilst the primary legislation makes it an offence to create or extend regulation 8 private water supplies, unless exempt under specific regulations, they must nevertheless be regulated as private supplies in accordance with regulation 8 where they exist. This at first seems counterintuitive. However, this is because the purpose of the Regulations at their inception in 2010 was firstly to facilitate a means to regulate onward distribution to protect consumers, but importantly and secondly, to seek them out to remediate their unlawful nature, and in so doing make them completely obsolete in time. Unfortunately, in the absence of any supporting mechanisms in place to achieve this, these secondary intentions were overlooked and have never been actioned or realised.

This review also identified that water resale supply arrangements, which are permitted under drinking water competition legislation, must be regulated as private supplies in accordance with regulation 8. Whilst the charging for onward distribution of water by a third party in this way is controlled by The Water Resale Order 2006, their creation or extension is nevertheless an offence under section 66(I) of The Water Industry Act 1991 (the Act). New Appointment and Variation (NAV) supply systems (Insets) also involve the resale and onward distribution of water from a water company’s supply system by a third party. However, they differ in that they are provided under licence by the economic regulator. This makes them public supplies, which are regulated by the Inspectorate. Any further distribution of a NAV’s system by someone other than the NAV, would however constitute a regulation 8 supply on its creation, and an offence under the Act.

Regulation 8 is itself difficult to apply in that it does not set clear criteria to determine where the further distribution of water by someone other than a water company is in scope and where it is not. Furthermore, the Regulations currently make no provision for local authorities to charge and recover some of the costs of their activities in association with regulation 8 supplies. These matters create confusion and frustration for stakeholders, leading to numerous enquiries and pleas to the Inspectorate to facilitate changes to the legislation, which it has no powers to do.

In 2024, as well as meeting with Defra colleagues to raise awareness of the apparent misalignment of legislation, the Inspectorate also presented at various stakeholder fora to explain the legislation and help provide some clarity. These included those made to The Chartered Institute of Environmental Health, Water Regs UK and several water company health liaison meetings. In 2025, The Water Health Partnership in Wales initiated plans to develop guidance on the application of regulation 8. This intends to establish a consistency of approach between the local authorities and water companies in Wales. The Inspectorate is represented on this ‘task and finish’ group.

In 2025, The Water Health Partnership in Wales initiated plans to develop guidance on the application of regulation 8. This intends to establish a consistency of approach between the local authorities and water companies in Wales. The Inspectorate is represented on this ‘task and finish’ group.

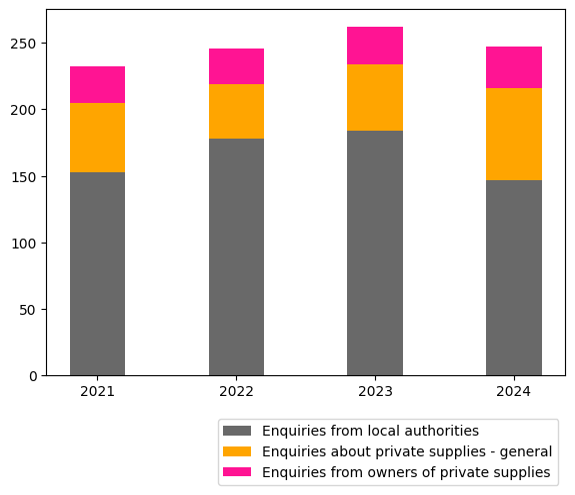

A significant amount of inspectors’ time is spent each year providing guidance on a case-by-case basis by responding to enquiries. These enquiries comprise both phone calls and email contacts. Unsurprisingly, the majority have been consistently from local authorities since the inception of the Regulations in 2010. The nature of these enquiries is variable, with some regulations attracting more enquiries than others.

In recent years, the Inspectorate has received several enquiries from local authorities requesting risk assessment training or seeking direction on where this is offered. These enquiries reflect a lack of training provision available in the sector. The Inspectorate is aware that at least one local authority may not be fulfilling its regulatory obligations due to not having sufficiently trained officers. Unfortunately, the Inspectorate is aware of only one training course that is made available to local authority officers in this key activity. The Inspectorate has had no sight of the content of this training and is therefore unable to comment on its suitability.

Some enquiries suggest a misconception of the role of the Inspectorate by local authorities with regard private water supplies. Although the Inspectorate offers technical advice on the application of the Regulations through its website and the enquiries line, it has no statutory duties beyond the collection of annual private water supplies data from local authorities, to provide an annual report on the quality of private water supplies in England and Wales, and to confirm (or not) any section 80 notice appeals that it receives. It has no remit to provide training or to facilitate improvements where they are needed. These are highlighted in the plethora of case studies that the Inspectorate publishes on its website. New case studies covering 2024 can be found here.

The Inspectorate is aware through enquiries that some local authorities are declining sampling requests from property owners or occupiers who are served by a private supply. The reason cited is that the ‘service’ is no longer offered. This would suggest either a misunderstanding of the regulatory requirements, or more worryingly that duties are knowingly not being fulfilled. It is of great concern that private supplies functions are knowingly being cut or closed when these functions are a statutory requirement. Unfortunately, the Inspectorate has no powers to investigate these reports, or those that are complaints about local authorities that have been unhelpful or have allegedly not met their regulatory obligations. Enquirers are reminded that each local authority has a complaints process which should be exhausted before contacting the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman.

Local authorities are encouraged to consult the Inspectorate’s website prior to making an enquiry on private water supplies. In 2022, a new search facility specifically for private water supplies was created to assist those visiting the Inspectorate’s website site to locate the information and relevant guidance they seek www.dwi.gov.uk/private-water-supplies/guidance-documents/.

Figure D Enquiries concerning private water supplies in England and Wales