Nitrate risks on a private water supply

Introduction

The Inspectorate has consistently observed and reported that there is a tendency for local authorities to rely on a reactive compliance-based approach to determine risk and apply enforcement. This is contrary to the risk-based principles of the regulations, which are intended to drive proactive elimination of potential risk using powers of enforcement where a potential danger to health exists.

The following case study illustrates the drawbacks of adhering to this outdated compliance-based approach by local authorities. It concerns a supply, where testing had highlighted elevated concentrations of nitrate. The local authority reasoned that the risks that this presented to consumers was low because some test results were below the standard, therefore consumers were not regularly consuming water with nitrate above the standard. On this basis they believed a regulation 18 notice was not necessary. However, prior to making any firm decision going forward, the local authority contacted the Inspectorate to seek their view by way of an enquiry.

Background

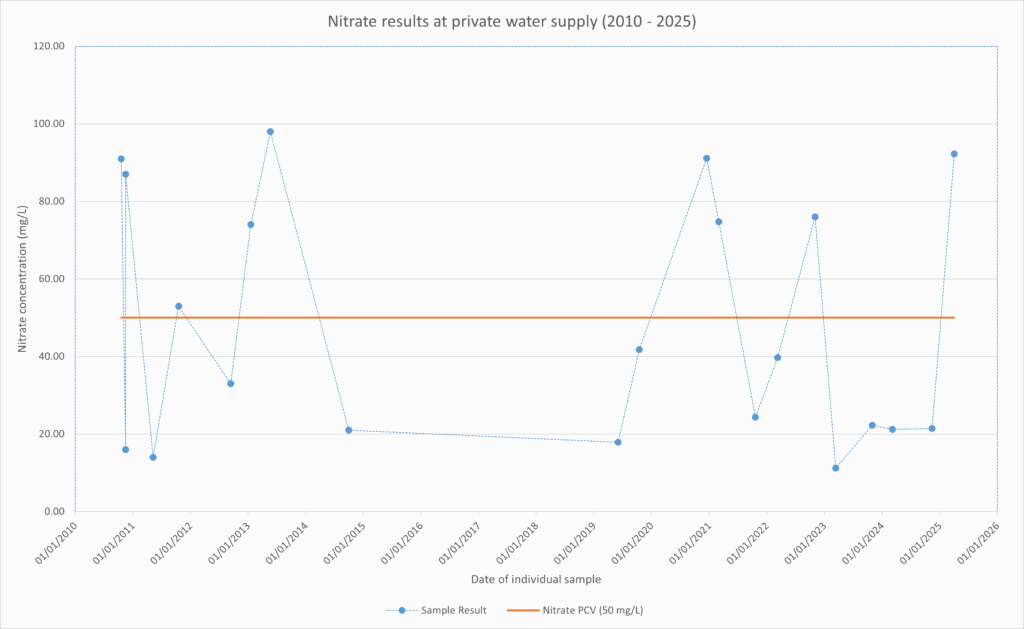

In June 2025 the Inspectorate received an enquiry concerning a private supply from which two samples exceeding the nitrate standard of 50 mg/L had been obtained (results of 76 mg/L and 92 mg/L inclusively). These samples were taken between 2021 and 2025. The results of four other samples taken within the same period were below the standard but nevertheless were elevated and potentially concerning. These ranged between 11 mg/L and 39 mg/L. Details of the health implications of nitrate in the drinking water above the regulatory standard can be found here.

This supply was being used commercially to serve a cheese production plant, but also for domestic purposes at 16 other properties, including a shop, an active village hall, a holiday let and tenanted dwellings. Consumers included an elderly tenant and others with various health issues. This constitutes a regulation 9 supply as it was (and is) being used as part of a public and commercial activity.

All samples taken were collected from the cheese production kitchen tap, except one that was taken from the cheese production office tap.

Using the local authority’s annual data returns over a wider period, between 2010 and 2026, the Inspectorate was able to plot the full set of regulatory nitrate results from this supply, against the 50mg/L nitrate standard. See graph below. This shows the occasions when nitrate exceeded the standard. Arguably the pattern for this could be considered as being “regular,” contrary to the local authority view.

Health advice

In 2022 The local authority sought health advice from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) in regard of nitrate at the concentrations found. They were advised that as a precaution, it was recommended that no one drink this water on a regular basis and that an alternative suitable source of drinking water should be used. This particularly applied to young children and pregnant mothers, as it is likely that infants, young children and adults even with low dietary nitrate intake would exceed the acceptable daily intake when this water is consumed.

Local authority enquiry to the Inspectorate

The local authority was of the view that there was insufficient evidence from these sample results to justify the serving of a regulation 18 notice to “prohibit the supply.” This was because the supply had ‘only’ breached the 50 mg/L standard on two occasions, which they concluded was not indicative of the regular consumption of water containing nitrate above the standard. The local authority did not act upon the advice of the UKHSA but then sought the view of the Inspectorate in 2025 after additional failing test results.

The local authority also posed the idea of gathering further monitoring data by conducting additional nitrate sampling from different residential properties each month and asked if they were permitted to serve a regulation 18 notice, restricting use of the supply at only those properties occupied by vulnerable persons. The intention here being to require these relevant persons exclusively to install treatment at these specific properties. It should be noted that the Inspectorate does not advocate point of use as a method of treatment on individual properties where such advice is provided. See guidance here.

The enquiry made no mention of any risk assessment or its findings. It is possible that none had been done given that in 2024, 29% of private water supplies in England were yet to be risk assessed and almost 68% did not have an in-date risk assessment in place.

Inspectorate response

The Inspectorate clarified firstly that a notice was not primarily intended to prohibit the consumption of a supply, although it was necessary to include this on a notice as a short-term precaution to protect consumers, whilst a permanent solution was sought. A regulation 18 notice is a legally binding instrument intended to require remedial steps to secure a wholesome, risk-free supply. It is not a restriction of use notice.

The local authority was advised that an investigation of the cause was necessary in accordance with regulation 16 and that whilst this was ongoing, they must provide information to consumers in accordance with regulation 15. This requires that appropriate steps are promptly taken to ensure that consumers of the supply are informed of the danger to health and to provide advice to minimise any potential danger. This could include, for example, advice to restrict the use of the supply, consume only bottled water, to boil the water or indeed not use the water at all until further notice.

The Inspectorate welcomed the suggestion that the local authority monitor the supply further at different sampling locations to increase the data set and better understand the risk. This would constitute part of their regulation 16 obligations. However, notwithstanding this, the information to date, limited though it was, suggested that there was already sufficient evidence to indicate a potential, if not actual, danger to human health.

On this basis the Inspectorate advised that a regulation 18 was required, which it considered long overdue.

The local authority acted upon this advice and served a notice immediately.

Inspectorate risk rationale

The local authority had reasoned that the concentration of nitrate at this supply presented a low risk because ‘only’ two samples from six had breached the 50 mg/L standard. This, in their opinion, did not suggest regular consumption of the water in breach of the standards in the regulations. However, these samples were few and all taken in a very narrow window between March and October each year over a relatively long period (four years). Nevertheless, a third of those taken had failed the standard, and limited though the data was, nitrate concentrations were exceeding the standard. In the opinion of the Inspectorate, this posed an overall inherent risk and a potential danger to human health, particularly in view of the health advice from UKHSA, which worryingly had been given some years previously and to date not acted upon.

The judgment that the regularity of consumption presented a low risk in this case was based entirely on six sample results, which the Inspectorate believed was not taking a sufficiently wider risk informed approach. “Regular” in the view of the Inspectorate was a subjective term and consumers were using this water daily for various domestic purposes. Consequently, it was highly likely that water above the nitrate standard was being consumed, if intermittently due to possible seasonal variations or changes in catchment activities. A risk assessment is intended to investigate and inform any such risk in this respect. The completion of a regulation 6 risk assessment was not mentioned or provided as part of the enquiry.

As part of their risk-based reasoning, the Inspectorate advised that it was necessary to take account of the potentially large numbers of consumers on this supply, many being unsuspecting members of the public, some vulnerable, others already known to be. Additionally, the fact that the water was being used in food production for the wider public should also be taken account of, and the Food Standards Agency advised of the matter.

The Inspectorate did not consider it appropriate to serve a notice only at premises where vulnerable consumers were known to reside. This is because consumption of the water was unlikely to be limited to those property occupiers. Visitors, including other vulnerable and unsuspecting consumers (young infants and children in particular), needed to be considered, as well as future tenants. There was also a likelihood that other vulnerable and unsuspecting members of the public were consuming the water too, as it was being used as part of a public activity at the village hall.

A notice must be served for overall inherent risks on a supply as a whole entity, not parts of it where it is less likely to be wholesome due to lack of treatment.

Learning

Reliance on testing in the way that this case study shows can compound and prolong the exposure of risk to consumers. It can also lead to ill-judged conclusions of risk. The information that any sample provides is limited, representing the quality of the water only at the precise moment it was taken. The information this provides is also limited by the number and range of parameters being tested at the time and may not be fully representative of the catchment risks in the absence of a source to tap risk assessment. Regulatory monitoring is infrequent; at most it is carried out annually. Small, shared supplies are monitored only once in five years for a handful of parameters, which does not provide suitably sufficient trending data. Regulatory sampling too is often carried out at the same or similar times of the year, as this case study shows. This may not highlight intermittent issues or verify the effectiveness of treatment (or lack of it) during seasonal changes in raw water quality over a year.

Consequently, reliance solely or mainly on infrequent testing for this purpose does not afford adequate protection in the risk-based way that the regulations intend, as this case study illustrates.

Testing and compliance monitoring remains essential however for the purposes of verifying the effectiveness (or not) of treatment. It is also important for gathering data on the overall quality of private supplies in England and Wales for reporting purposes. Unfortunately, this data consistently shows that private water supplies overall, continue to present a potential health risk, although their quality has made some improvement since the regulations were first implemented in 2010. It is possible that the rate of this is being hindered because risk-based methodology and enforcement is not being fully applied when it is required.